FOUNDER, REAL MOTHER SHUCKERS

Lives In: Ocean Hill, Brooklyn

Working Toward: Reconnecting New Yorkers with their Oystering History

It is not uncommon for master (and motha) shucker Ben “Moody” Harney Jr. to hear the phrase “I hate oysters.” But instead of turning up his nose, the founder of the Real Mother Shuckers relates. After all, he didn’t start out a fan, either.

Transitioning from the nonprofit world in 2011, Moody started working at restaurants in Louisiana and Florida. While he enjoyed cooked oysters—say, battered, fried, and sandwiched in a po’ boy or stirred into a chowder—he thought the idea of eating a raw oyster was a “horrible” prospect. It wasn’t until 2018 when Moody started at Maison Premiere—the iconic French and New Orleans–styled oyster bar in Williamsburg—that he learned to respect the bivalve in its raw state.

Of his training at Maison Premiere, Moody says, “They asked us to flip and smell oysters. For the first time, I had to keep the bodies intact. When I was shucking in Louisiana and Florida, they really didn’t give two craps about how the bodies of the oysters looked, they just wanted them open.” Moody’s training also required him to familiarize himself with more than 30 varieties of both East and West Coast oysters.

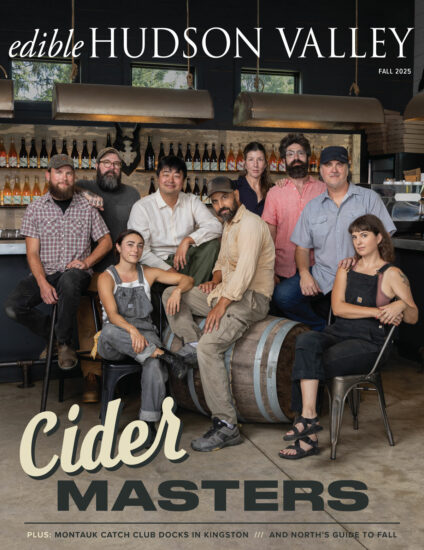

FEATURED IMAGE (TOP)

Icy Cool. Moody is reviving a nearly forgotten New York City tradition while plying a historically Black trade. His success has led to several prominent brick-and-mortar locations, plus, it paved a way for Moody to help New York City high school students.

Inspired, Moody dove into all things oyster and quickly discovered the shellfish’s rich historical ties to the city. In the 19th century, New York City was the oyster capital of the world, with more than 1 million bivalves being shucked, served, and slurped here every day. At that point—before human and industrial waste made them inedible by the first decades of the 1900s—oysters throve in the brackish waters of the New York Harbor, which produced up to 700 million oysters per year. Curbside stands and oyster cellars were mainstays of city life.

More than just a food, New York City’s oysters provided economic advancement for freed Black people. Fleeing restrictive laws in Maryland, Black oystermen settled in the Sandy Ground neighborhood of Staten Island in 1833. Supported by a booming oyster industry, the area became the first free Black community in New York State where members owned property, homes, and businesses. One of NYC’s free Black oystermen, Thomas Downing (1791–1866), known as the “Oyster King,” was a descendant of slaves who began his career raking up oysters that he sold on the street. In 1825, he opened the Thomas Downing Oyster House at 5 Broad Street. His establishment was a departure from the rough-and-tumble oyster cellars, which, frequently, were also operated by New Yorkers of African descent. Signified by red lanterns hanging outside, these drinking and raw oyster bars became known as “dives” for the act of “diving” downstairs to access their sub-pavement premises. In contrast, Downing’s restaurant was exclusive, and comfortable for women and children. He parlayed its success into an export business in which he shipped massive numbers of live, fried, or pickled oysters to Europe and the West Indies. He died one of New York City’s wealthiest men.

“I want to give people the opportunity to grab a plate of oysters during the summertime and run around with their pinkies up in the air.”

Paying homage to the streetside shuckers of New York City’s oystering heyday, Moody revamped an ice cream cart, turning it into an oyster cart. By 2018, Moody was roaming around the city, slinging oysters with a side of New York history outside of popular bars and restaurants. Nowadays, Moody has outlets all around the city, including at the Hudson-side food hall curated by the James Beard Foundation, Market 57, and at Industry City in Sunset Park.

Using his stature as a successful Black business owner, Moody has partnered with various New York City schools, teaching teenagers basic knife skills, food prep, and business management acumen. In this way, Moody is building a pathway for the next generation, giving budding chefs a head start or simply providing kids with a skill that they can use to get by with during hard times.

Moody’s primary goal is to make the oyster accessible to all—and, especially, to his own community given its historical connection to the bivalve. He’s currently leveraging city council members to fund oyster giveaways; meanwhile, he’s also looking to partner with food banks and the New York City Housing Authority to do the same. Yet, while crab and shrimp are popular in Black communities, the oyster has yet to (re)cross the color barrier. Nevertheless, Moody believes that oysters—once a common man’s food—could become accessible once again.

“I want to give people the opportunity to grab a plate of oysters during the summertime and run around with their pinkies up in the air.”